Research

Visual processing in naturalistic stimulus and behavioral contexts

The kinds of visual stimuli that are often shown in a neuroscience lab are very different than visual stimuli out in the real world. For one thing, the structure of the world (e.g. the sorts of contrasts, colors and orientations that exist in the real world) may be very different than what is seen in typical visual neuroscience stimuli. For another, real visual input is in almost constant motion, due in large part to the motion of the animal itself. How do brains deal with the complex and dynamic conditions that characterize natural vision? We use the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, as a model to ask this question. Working in flies allows us to make genetically targeted recordings and perturbations for virtually any neuron of interest, and because we have the fly connectome, we can know every neuron’s inputs and outputs. This allows us to study neural computation with spectacular precision at the circuit, cellular, and synaptic level.

A fly’s visual system is in many respects quite different than our own, but there are powerful constraints that are shared across very different species, from flies to humans. For example, the same physical laws that underlie the statistics of scenes encountered by flies also shape the scenes humans encounter. These statistical regularities can constrain neural processing strategies. This simple fact allows us to learn general principles of natural vision by looking at the different behavioral demands and associated neural processing strategies that different species use.

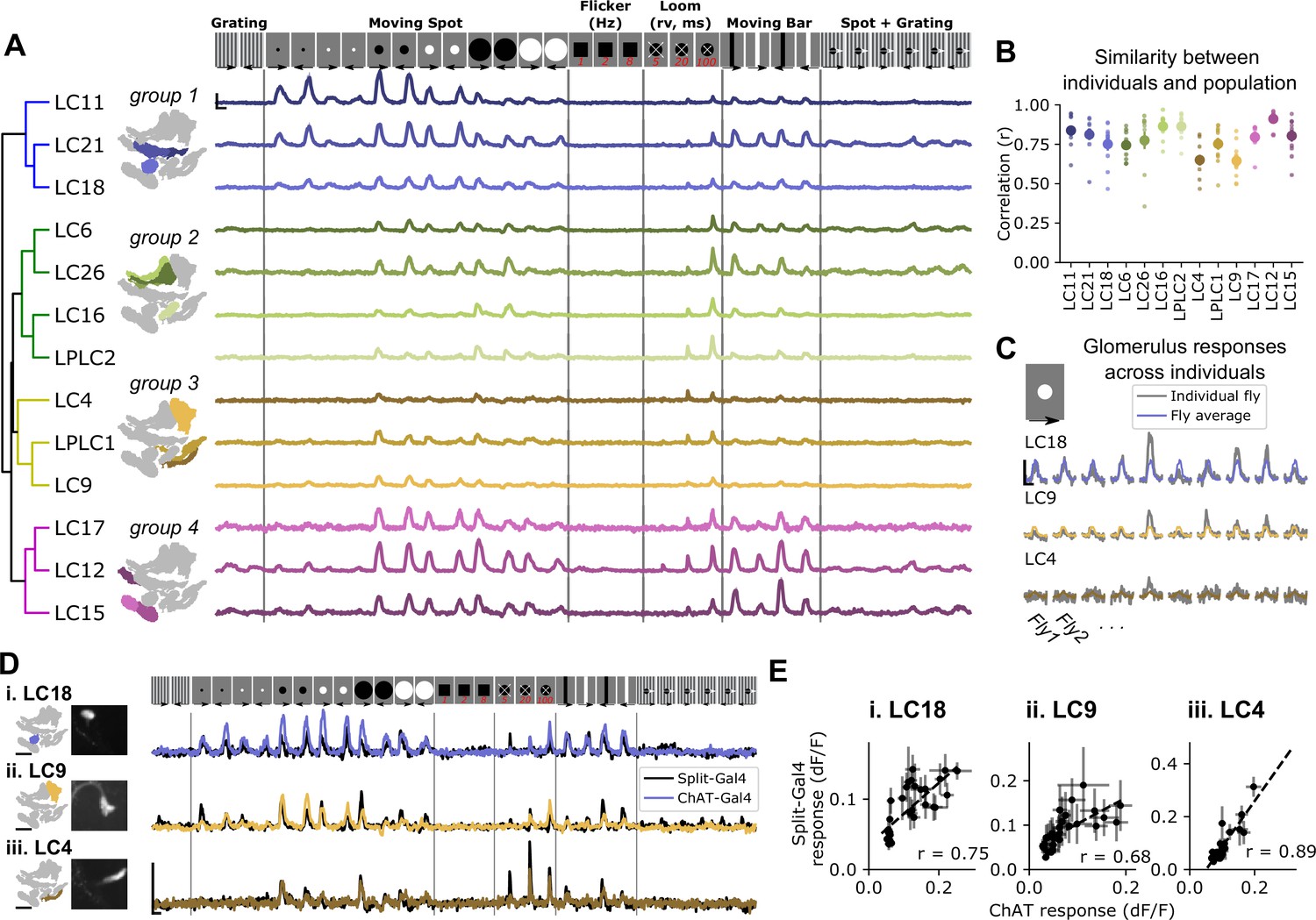

Population representation in Drosophila visual projection neurons

Visual scenes are composed of many features that overlap in time and space. Visual systems often parse complex scenes into their component parts, which are then represented by distinct pathways and neural populations. Drosophila Visual Projection Neurons (VPNs) transmit highly processed visual information from the optic lobes to the central brain, where that information is used to guide behavior. Work from our lab and others suggests that it is combinations of activated VPNs that drive visual feature perception, in a population code. In order to understand how diverse VPNs represent complex scenes, we are using new imaging and analysis methods to measure neural activity across many VPN populations simultaneously. This provides a way to characterize VPN population responses and relate them to stimulus statistics and animal behavior in real time.

Highlighted publications

Structure-function relationships in the Drosophila Brain

The anatomical structure of neural circuits can strongly constrain the function of those circuits. Because of this, neuroscientists have long used nervous system structure to guide investigations of function (and vice-versa). In the age of large-scale connectomics, we need to figure out how we can use precise anatomical information to help us understand neural computation. This presents some conceptual as well as technical challenges. We use the wonderful connectome datasets available in the fly brain to explore how we can leverage this unprecedented access to structural information to better understand how the brain works.

Highlighted publications